Chris Schopf, Achieva’s Vice President of Community Supported Living, was on grandma duty at a trampoline park when her phone started buzzing.

On that same Saturday morning in October 2018, Marte Novak, Achieva Community Inclusion Manager, answered a call and began praying with the person on the other end of the line.

Michelle Stockunas, former Vice President of Home and Community Supports at Achieva, was running at the gym right around the same time when she noticed a crowd staring at the TV screens that dotted the wall.

There was an active shooter at Squirrel Hill’s Tree of Life Synagogue during Shabbat service.

“I immediately got off the treadmill and started texting people because I knew Cecil and David Rosenthal were there,” she said. “They never missed.”

Cecil was a greeter at the synagogue each and every Saturday — a role tailor-made for his welcoming spirit, as most will attest. David handed out prayer shawls and Torahs to old friends and new ones – for both boys, there wasn’t a difference between the two.

But on that particular day — Oct. 27, 2018 —they likely greeted a man who’d prove to be neither. As determined by federal court convictions in June 2023, he killed 11 people inside the synagogue that day, including Cecil and David.

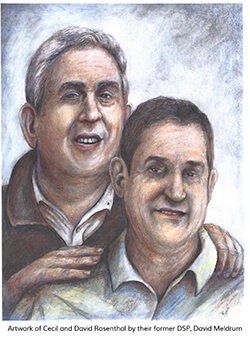

The Rosenthal brothers — affectionately referred to as “the boys” by those who knew them best — have had their story shared by many since that devastating October day.

Maybe it’s because they’re brothers, making the loss for their family doubly catastrophic. Maybe it’s because they were both born with Fragile X syndrome, a genetic disorder marked by intellectual disability, among other differences.

But more than either of those reasons, it seems that people return to the boys’ stories because of the void their losses have left — one so vast, even their family were awed by the impression they’d left on the world.

Despite their differences — or maybe because of them — Cecil and David taught a masterclass on love and connection. As a result, their “community” isn’t just a pocket of people in their immediate vicinity but more of a far-reaching, wide-ranging chain, including those they shared a bus with, to decades-worth of caregivers and co-workers, to their parents’ neighbors and sisters’ friends, to local florists and first responders, all of whom became family.

So, when you hear that Cecil and David Rosenthal are missed, know the depth of that sadness was earned by the pureness with which they lived. Here are those stories.

‘He’ll never be a famous person’

“They were born for a reason: Because they’re special,” said the boys’ mother, Joy Rosenthal. “They were given to us because they were special. And when we received them, we were told to put them in an institution.”

From the moments Cecil and David Rosenthal were born — about five years apart in the early 1960s — they already stood out.

Doctors found anomalies in their physical makeup but nothing they could identify by name. There was little mention of any associated intellectual or emotional differences. It wasn’t until the boys’ uncle, a forward-thinking pediatrician from Arizona, ran blood work in their early childhoods that “Fragile X syndrome” entered the conversation.

Once it was, the next piece of advice was to institutionalize them.

“Our parents said we’re a family. All four of our children will be raised together,’” the boys’ sister, Diane Rosenthal Hirt recalls. “[Our sister] Michele and I don’t feel like we gave anything up at all, but our parents put a lot of time and resources into our brothers to make sure they didn’t need to be institutionalized and we could remain as a family.”

Though options to support them were few, Joy and her husband, Elie, found schools and summer camps suited to their sons. For many of those educators, it was enough to know that the Rosenthal boys were different, but one particular nun wanted to know more.

She used the testing resources available at the time, and in Cecil, found a “learning disability,” which would prevent him from reading or writing. “He’ll never be a famous person,” she said to further explain his differences.

The decision to keep the family together and focus on the boys’ abilities, the Rosenthal sisters now know, defined the rest of Cecil and David’s existences.

“I think it all goes back to my parents,” Michele Rosenthal said. “I think because of how my parents raised all of us, that in their eyes, there was no difference between us.”

Who cared for whom?

“We always tried to mainstream the boys as much as possible, taking them out into the community, introducing them to people, and they made their own lives from there,” Elie said.

“We would take them shopping or something, and people would come up to him, ‘Hi, Cecil. How are you?’” Joy remembers. “We’d ask, ‘Who was that?’ And he’d tell us. They knew people, and people knew them.”

Marte Novak was the now-closed Strip District workshop plant manager while the boys worked there. Like any manager of anything, some days had challenges.

Marte is known for her pleasant disposition. She likely hid the tough days well, but not from the boys.

“One of the things that I think was uncanny was that both of the boys could feel the energy of me,” she said. “They would notice my mannerisms, and immediately, in a boisterous voice, Cecil would say, ’Well, hello pretty lady,” and totally bring me back to make sure I recognized that he was there. He was making sure I was OK.”

While working at the same facility — which repacked bottles for Iron City Brewing, worked as a mail service, and packed Turbie Twists hair towels, for example — Cecil took folks in the School to Work Transitioning Program under his wing.

Had he taught the rules in a matter-of-fact manner, no one would have objected. But he took a much gentler approach, all on his own.

“In a jovial way, he would say, ‘You don’t want to do that. The boss lady wouldn’t like that,’” Marte remembers. “He was redirecting them without being bossy.”

At the boys’ community home, run by Michelle Stockunas at one point, Cecil’s manner was equally therapeutic.

“If he’d see you were having a busy day, he’d definitely provide stress relief. He’d see you coming through the door and say, ‘What are you doing? Your hair’s a mess,’ or something else funny,” she said. “Or he’d shake your hand and want to sit down with you and talk about fun things we’d be doing in the upcoming month.

“I think he took care of everyone else as much as we were there to support him.”

David

Cecil’s booming personality attracts a lot of fanfare, earning him the title “the mayor of Squirrel Hill” in some circles.

David was different.

Like many of the protectors in our society, his work for civic betterment existed below pop culture’s radar.

As a young boy, he was fascinated by the Pittsburgh Press delivery boy’s work.

“He let David carry the canvas Pittsburgh Press bag that carried all the papers, and he let David throw all the papers up to the customers on the street,” Elie said. “When he came home, he was so proud. The newspaper boy gave him a dollar for helping him,” which was a handsome sum at the time. Elie said thank you for his kindness by replacing that dollar and then some.

David also loved to watch the family’s landscapers. They’d give him a rake, and he’d join their workforce. And when they paused for lunch, David ran inside to make his own sandwich, which he enjoyed with the other guys in the shade between the houses.

“This was his assimilation into the community,” Elie said.

As an adult, he befriended the local police and firemen, disappearing to their precincts for hours at a time.

“Those guys truly took him in,” Diane said. “I think he felt a sense of importance in protecting people, and a sense of responsibility and doing something good,” which his friends repaid to him when he needed them most.

Several years ago, David sustained a brutal physical attack while downtown. During his recovery at home, the local hook-and-ladder truck pulled up in front of his parents’ house. The firemen poured out of the truck and delivered a fruit basket.

“Look what my friends brought me!” David gushed. It was a meaningful comment from David for whom “friends” were earned, not assumed.

“He would kind of hang back until he got to know somebody,” Michelle Stockunas said. “But once you got to know him, he was the same as Cecil.”

Once you got to know him, you also learned what scared him: thunderstorms.

“That’s one of the things that always bothered me about what happened,” Michelle said. “He was scared of storms, and he had to face the biggest storm that he’ll ever encounter.”

‘That’s what they taught us’

“They had the personalities that God gave them, and they used them to their finest,” Joy said. “I think Achieva put it best, ‘Love Like the Boys.’ If somebody’s behind you, give them a coupon or pay for their coffee. Or open the door. Be kind. That’s all.”

Cecil and David’s genuine and kind natures might have been God-given, but they were perfected by those who surrounded them.

They’re the children of pioneering advocates for disability equality, though Elie and Joy would say no such thing. They simply loved their children equally.

While being exposed to the best resources available — through Achieva and other organizations — the boys lived to their abilities: riding busses, greeting fellow worshipers, working in offices and on janitorial staffs, throwing parties and hosting friends for any and every occasion, and becoming keepers of stories as their communities’ confidants.

As the universe would have it, their kindness and genuineness attracted much of the same in those who surrounded them. And as good humans often do, those people searched for even the slightest glimmer of a silver lining in the tragic loss of the boys.

Their sister Diane says thank goodness the boys did not have to go on living without the other. Knowing how deeply connected they were to their faith and synagogue, Achieva’s Chris Schopf said, “They were where they were supposed to be that day” because they wouldn’t have been anywhere else on Shabbat.

And though the void left by their loss is boundless for those who loved them, family and friends have attempted to fill the space just as the boys would have, by bringing people together.

Privately, their sister Michele makes “an effort every day to do something consciously to love like Cecil and David.”

“It is complimenting somebody. Smiling at somebody. Being kind to somebody you can tell is having a bad day,” she said. “Sure, it’s paying for someone in the Starbucks line, but the most important thing is truly weaving kindness into your life,” which is the spirit behind the public #LoveLikeTheBoys campaign.

The movement encourages anyone … everyone … to perform random acts of kindness with Cecil and David in mind.

That love-in-action can be posted to social media and tagged with #LoveLikeTheBoys. It can include printable LLTB cards available on the Achieva website. Or a good deed can be done with no bells or whistles at all, save for your best intentions.

Another way to remember the boys out loud is The Cecil and David Rosenthal Community Award. Presented each year since 2018 during Achieva’s Awards of Excellence, the award honors a person with intellectual or developmental disabilities who, like the boys, have intertwined themselves with the community in unmissable ways.

And for those on the receiving side of assistance, the donor-supported Cecil and David Rosenthal Memorial Fund supports community engagement activities — iPads, specialty speech therapy, Kennywood passes, Lyft and Uber gift cards, and more — for those with intellectual disabilities and/or autism in 12 Pennsylvania counties.

To those who knew them, there’s no better way to honor Cecil and David.

“Cecil would have been so excited to know that people are connecting with each other. I think he would have found that to be really incredible,” said Achieva’s Marte Novak. “It is such an amazing use of those dollars.”

“They’d be so thrilled to know the impact they’re having,” said Terri Bohn, former Community Home Specialist, who retired after 34 years with Achieva. “Cecil would be the first one to pass everything out.”

Maybe that it isn’t the same brand of fame Cecil’s elementary school nun referred to — the kind reserved for actors or politicians — but to those who benefit, there’s maybe no greater form of heroism.

“They’re always with us in spirit. Love Like the Boys gives us a mission, and leaves a legacy for the boys,” Diane said. “‘I did something special. I left a legacy.’ I can see them looking down on us to say something like that.”